Surviving Twice

Surviving Twice Trin Yarborough’s Surviving Twice provided a thorough overview of the Vietnamese Amerasian experience during the past 50 years. Apart from outlining historical events, her book provided rich perspectives on the concepts of race, poverty, family, and exploitation through the eyes of six Vietnamese Amerasian informants. Some of her contributions to the knowledge on the Vietnamese Amerasian follows:

Amerasians in Viet Nam served as a reminder of a war lost (45).

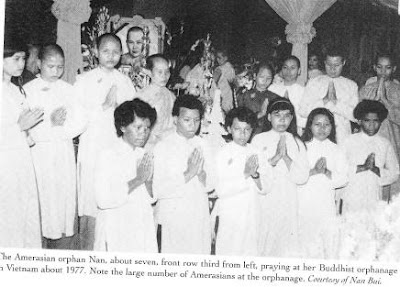

Their mothers, many of whom had legitimate relationships with American men who had promised to bring them to the United States, were laughed at and labeled loose and prostitutes. Fear of having an Amerasian child, especially a black child, and facing additional prejudice and disapproval in an already impoverished South caused many women to abandon their children to orphanages (20). Many Amerasians ended up homeless and having to fend for themselves (97) until the passage of the Amerasian Homecoming Act in 1988.

Growing up after the war, the children were called “bui doi,” literally dust of life/ dust children (157), and many were mercilessly teased and beaten (58). Robert S. McKelvey's book, Dust of Life, also addresses this.

In a nation where whiteness has long been associated with divinity, beauty, and being angelic (88), the situation was worse for black children. Being called “Black” in Viet Nam can roughly be translated of being called “nigger” or "savage" in the United States (87, 85) and many Amerasian children were either denied an education or treated unfairly by classmates and teachers, resulting in high rates of drop outs and illiteracy among Amerasians(86).

Echoing what I’ve heard from my own grandmother about what the post-war period was like for South Vietnamese and those associated with American imperialism, one of Yarborough’s informants explains “My mother had burned almost all the pictures of my dad in 1975 because if you had a picture of an American they would put you in jail.” (198) Up to 58 percent of Amerasians know nothing at all about their fathers (138).

Gold children

After the passage of the Homecoming Act however, many Amerasian children, long abandoned and mistreated were showered with gifts and bribes from both family members and outsiders hoping that they would claim them as a relative and bring them to the United States (111-113). Once in the United States, the Amerasian teenagers or young adults, many whom had no actual family, were often again abandoned by their “families (153).”

Having no one and lacking education and English skills (199, 209, 244), many faced their second bout of poverty, depression, and abandonment in their father’s homeland (153, 171-172). Many idealized their fathers as brave and upstanding men who loved their mothers, but only 2 percent were ever able to find their fathers, and many soldiers had either died or did not want to be presented with a reminder of a dark period in their lives.

Although her position as an outsider led Yarborough to make some over-generalizations about Vietnamese people, the war, Amerasian and “culture,” her work brought to light the similarities or prejudice against blackness that exist in both nations. Although contact with American culture was limited before the war, once soldiers arrived, bars where women worked were divided into "White" bars and "Black" bars. Some Vietnamese even saw having a half white child as a status symbol (17).

As an aside, I find it necessary and crucial to compare the parallels between the experience of inequality black soldiers faced while serving during the Civil Rights movement to the experience of some of their children as a measure of how history repeats itself.

Yarborough, Trin. Surviving Twice: Amerasian Children of the Vietnam War. 2006. Washington D.C. :Potomac Books. Print.